Thanks to Karen Burch for sending me the text of this June 18, 1937 Daily Worker interview with George Washington Albright.

————————————————–

A 91-year-old Negro who played a major role in the events of the Civil War and Reconstruction passed through New York this week on his way from Colorado to Washington and told his story in an extended interview with the Daily Worker.

At the home of his granddaughter in Jamaica, Long Island, George Washington Albright, born a slave in Mississippi, related a personal history which is at the same time one of the most revolutionary eras in America’s past.

At 19, Albright was a secret runner for the Lincoln League, carrying from plantation to plantation the news that the Emancipation Proclamation had been signed in Washington. In 1865 he was a field hand on a cotton plantation; nine years later he entered the Mississippi Senate as a member of the Reconstruction government.

Today, Mr. Albright follows the struggle for Negro rights with intense interest, and is well informed on current events. He asked questions about the Southern Tenant Farmers Union in Arkansas, and wanted to know what steps were being take to bring to trial the men who attacked Claude Williams and Willie Sue Blagden, union representatives in Arkansas. He praised the Communist Party for twice nominating James W. Ford for the vice-presidency.

“That was a great act,” he said. “your party showed the world where it stood.”

Asked why he had recently abandoned the Republican Party, in whose ranks he served for more than half a century, he replied:

“Do you suppose that at my age I can’t tell the difference between a Lincoln Republican and a Landon Republican? Look at all the rich Democrats who’ve jumped out of the Democratic Party into the Republicans’. The Republican Party has turned against the common fellow, and I’ve turned against the Republican Party.

FAMILIES PARTED

“When I was born, in 1846, on a plantation in Holly Springs, Mississippi, my mother and father were held by different owners, and when I was 11 years old, my father was sold to a man in Texas. It’s said today that the slaveowners did not separate families, but actually a plantation owner thought no more of selling a man away from his wife, or a mother away from her children, than of sending a cow or a horse out of the state.

“It was only by trickery that I learned to read and write. There was a law on the Mississippi statute books, that if any slave learned to read or write, he was to be punished with 500 lashes on the naked back, and to have the thumb cut off above the second joint. If any master allowed his slave to read or write, he was required to pay the state $500 in damages.

“However, the white children on my plantation often did their lessons in the kitchen, in my mother’s presence and she picked up what information she could, and taught me. I got a primer, and learned to read it.

LEARN OF JOHN BROWN

“We slaves knew very little about what was going on outside our plantations, for our owners aimed to keep us in darkness. But sometimes, by grapevine telegraph, we learned of great events.

“It was impossible to keep the news of John Brown’s attack on Harpers Ferry from spreading. That attack threw a scare into the slave owners. One day not long after the arrest of Brown, a boy in a nearby orchard shot off a pop gun and my mistress ran in terror to the house, screaming that the insurrectionists were coming.

“Like many other slaves, my father ran away from his plantation in Texas and joined the Union forces. I found out later that he was killed fighting in the battle of Vicksburg.”

“When the Emancipation Proclamation was signed, the plantation owners tried to keep the news from us. The Washington government, however, organized an underground information service to inform he slaves of their freedom.

“The slaves, themselves, had to carry the news to one another. That was my first job in the fight for the rights of my people – to tell the slaves that they were free, to keep them informed and in readiness to assist the Union armies whenever the opportunity came.

“I was 15 years old when I became a runner for what we called the “4-Ls” – Lincoln’s Legal Loyal League. I traveled about the plantations within a certain range, and got together small meetings in the cabins to tell the slaves the great news. Some of these slaves in turn would find their way to still other plantations – and so, the story spread. We had to work in dead secrecy; we had knocks and signs and passwords.

“It wasn’t until many years later that I found out how the 4-Ls had been organized. It was started after a committee of six went to Washington to see Lincoln for that purpose.

PROMINENT GROUP

“On the committee was Frederick Douglass, John Langston and James Lynch, outstanding Negro leaders and three white Abolitionists – Henry Ward Beecher, Charles Sumner and Mrs. Harriet Beecher Stowe. This committee asked Lincoln to put the Proclamation into effect by informing the slaves. Emissaries were sent out from the North to start the word on its way.

“Speaking of Mrs. Stowe reminds me of how a Northern man put into my hands a copy of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, and how I read it secretly at night. That was while the Civil War was still going on.

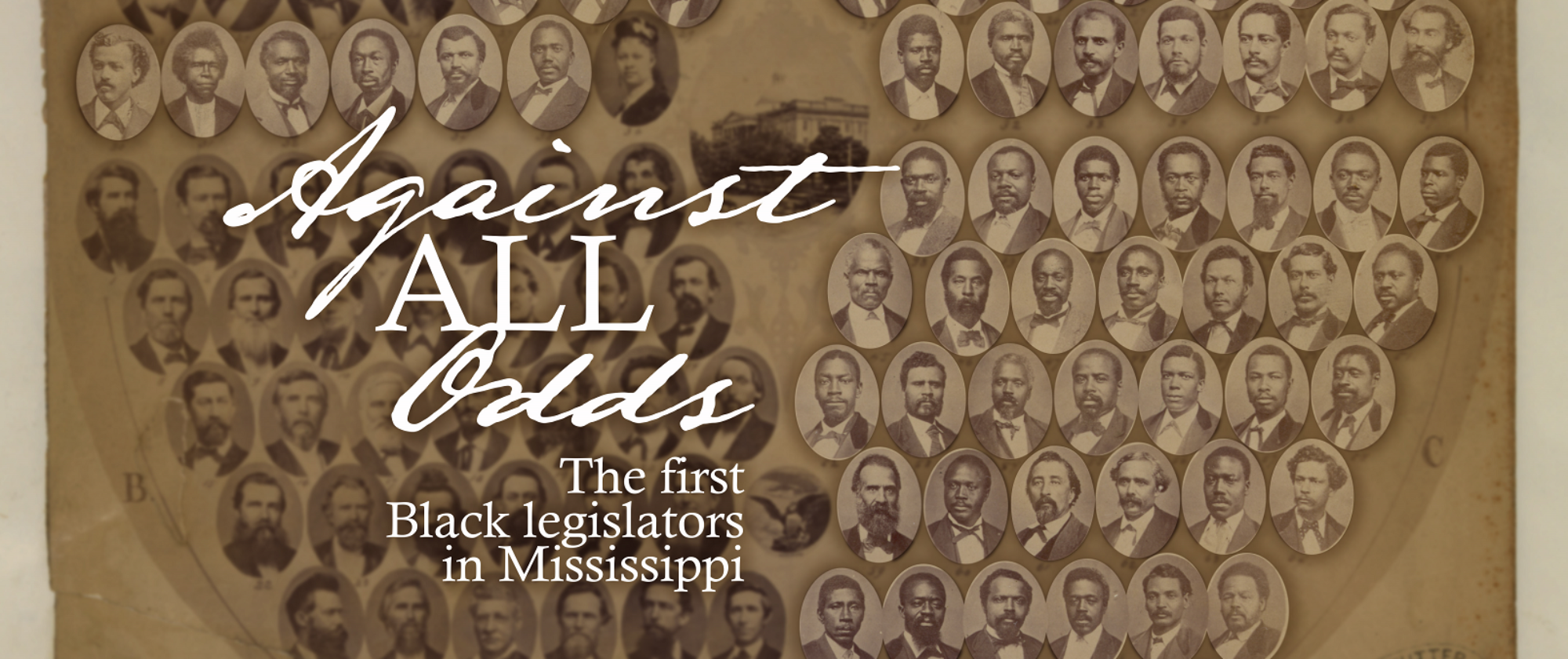

“I wasn’t a member of the Constitutional Committee that met in Jackson, the state capital, in 1868, to draft a new constitution for Mississippi, but I helped to elect some of the members to that convention.

“It was the first legislative body in Mississippi in which Negroes took part –think of that, in a state which had a majority of Negroes! There were 74 Negroes out of 100 delegates to that convention. Five of those Negroes were murdered within the next few years by reactionary white planters.

“No wonder the plantation owners hated that convention, and hated the legislatures that followed it. No wonder the rich folks hate the memory of those legislatures to this very day! The convention made a new constitution, the first in the history of the state under which poor people, white and Negro, had any rights.

“Before that time, only the plantation owners could hold office in the state. By the new constitution, there was to be no property qualifications for holding office or for voting.

“The new constitution of our state stopped all the discrimination against the Negroes to travel, in hotel accommodations, in the right to give testimony in court, in the right to vote and serve on juries. The poor whites who sat in the convention favored these measures as much as did the Negro delegates.

40 NEGROES IN {THE} LEGISLATURE

“In the very first state legislature that was elected under that constitution there sat 40 Negroes. Every one of the 40 was just out of slavery.

“A Negro, Hiram Revels – I knew him very well – was elected to fill the unexpired term of Jefferson Davis, who had been president of the Confederacy. That was enough to make all the dead slaveowners turn over in their graves.

“I myself was elected to the Mississippi Senate in 1874, being one of the nine Negro Senators. I served four years. I cast the first vote for Blanche K. Bruce, a Negro who succeeded Hiram Revels in the Senate. Both Bruce and Revels made a brilliant showing in Congress.

“One of the first things we did in that legislature was to take steps to wipe out the state debt. There was a lot of talk among the plantation owners about our ‘extravagance,’ and people even today try to discredit our rule at that time by saying that we spent money right and left, wasting the state’s resources. As a matter of fact, the tax rate in Mississippi was less than nine mills on the dollar, and one-fifth of the total we collected was for schools.

“We issued money which became known as ‘Alcorn money,’ after the Republican governor, J. L. Alcorn. We retired it at 25 percent each year until every dollar of debts the state owed was wiped out. Out of that money we built roads and schools and hospitals, trained teachers, kept the state running.

CIVIL RIGHTS BILL

“Our legislature also enacted a Civil Rights Bill that Congress passed. That bill gave equal rights in all fields to every person in the state, regardless of race, creed, color, or previous condition of servitude. But the Supreme Court which was with the slave owners and against us, threw out the national Civil Rights Bill, and that wiped ours out too.

“I taught the first public school in Mississippi. We held our sessions under a shade tree, and later in a cabin, and still later in an old abandoned church.

“The state had no teachers, and we brought in teachers from the North, men and women, white and Negro. The rich whites ostracized these Northern teachers, and tried to make their life hell for them. They called the Northern teachers carpetbaggers, as they did everyone from the North who treated Negroes on a man-to-man basis.

LEGISLATURE BUILDS SCHOOLS

“Before the Civil War there wasn’t a free school in the state, but under the Reconstruction government, we built them in every county, 40 in Marshall County alone. We paid to have every child, Negro and white, schooled equally. Today, they’ve cut down on the educational program, and discriminated against the Negro children, so that out of every educational dollar, the Negro

child gets only 30 cents.

“I became trustee of the State Normal School. We paid off every debt we contracted, and when I turned in my financial report in 1874, there was $150 left in the treasury. I helped supervise the budgets for other higher schools and by careful accounting saved the state more than $30,000.

“We had Negroes in many responsible positions. A Negro was lieutenant governor – his name was Alex Davis and Negroes also filled the offices of Secretary of State, Superintendent of Public Instruction, and Commissioner of Immigration.

ORGANIZE MILITIA

“I helped to organize the Negro volunteer militia, which was needed to keep the common people on top and fight off the organized attacks of the landlords and formers slave owners. We drilled frequently – and how the rich folks hated to see us, armed and ready to defend ourselves and our elected government!

“Our militia helped fight off the Klan which was organized by the old slaveowners to try to make us slaves again in all but name.

“I had a couple of narrow escapes from the Klan myself. When I began to teach school, the plantation owners said: ‘That Albright is a dangerous nigger. He’s a detriment to the state.’ One day I got a warning from a friend that I’d better sleep away from home. I took the hint. Sure enough, that night the Klan came to the house and asked for me. My sister said she didn’t know where I was.

“Let me tell you also the story of a friend of mine by the name of Zeke House. Zeke House was a Negro mail carrier. One day, while he was carrying the mail from Holly Springs to Waterford, the Klan seized him and murdered him in the woods, and left him in a ditch. We found his body days later. That was in 1874.

“Another friend of mine, Charles Caldwell, who was a captain of the Negro militia and a member of the Mississippi Senate, was murdered by the Klan also.

“The rich people regained control over Mississippi with the help of the Klan. Unfortunately, they got many of the poor whites on their side. The poor white people felt that their interests lay with the Negroes – for the first time they had voting rights, and school for their children. But the landlords kept poisoning their minds, saying, “You’re voting with the niggers. You’re lining up with niggers.’ The landlords split many of them away from their own best interests.”